By: Xu Li, former Vice Chairman of the China Artists Association

When the Hong Kong gallery Tsikuchai opened An Extraordinary Tour of Art in February 2025, it was more than a solo exhibition. It was the unveiling of an artistic journey that reflects literati traditions, cross-cultural exchange, and an emphasis on art as a lived practice. The show presented Jingwei Zeng not only as an artist but as a curator, educator, and cultural activist—someone who strives to keep literati aesthetics alive rather than letting them fade into footnotes of history.

A Lineage of Devotion

Zeng’s path began at home, under the patient discipline of his father, Zeng Wenhua. A late-life parent, his father dedicated himself entirely to his son’s education—waking him before dawn to practice calligraphy under a tree, composing poetry with him in a bamboo grove, and teaching him that art was not merely skill but a way of living. The family’s sacrifices—brushes over comforts, poetry over leisure—are etched into every stroke of Zeng’s hand. That foundation, supported by his mother’s quiet constancy, was less about training and more about cultivating resilience, humility, and reverence for tradition.

Independence and Companionship

Unlike many who pursue institutional recognition or the security of associations, Zeng has chosen to build his career on independence. He has avoided the temptations of fame, even when showing at international fairs like the Louvre’s Art Shopping. His compass is not external validation but an inner devotion to literary ideals.

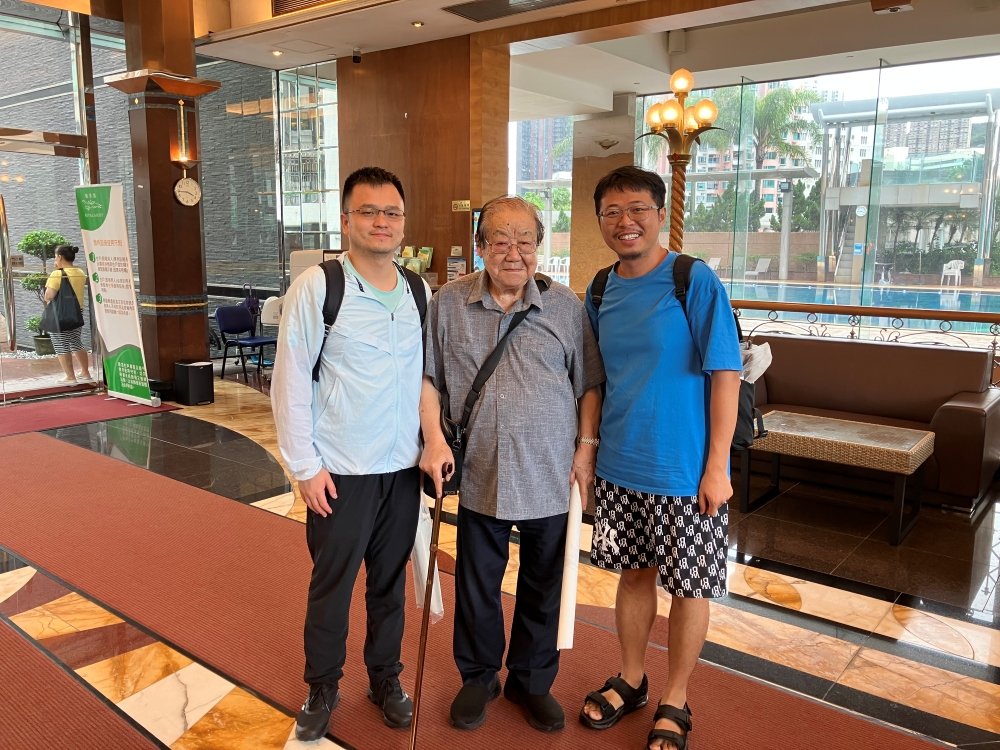

Photo Courtesy: Jingwei Zeng (Professor Ambrose King Yeo-Chi with Jingwei (right) and Longqiang (left), Hong Kong, 7/22/2025)

This independence stems from a strong companionship. At crucial moments, Zeng has received support that is remarkable by any measure. Among these relationships, his bond with Yang Longqiang stands apart (Figure 1). Yang’s commitment was not confined to financial or logistical help during Zeng’s studies in the United States. It extended into something much rarer: a shared spiritual and intellectual resonance. Together they traveled to museums to study masterworks firsthand, conducted research side by side, held long dialogues with artists, and supported each other through exploration and discovery. Yang’s care even reached into Zeng’s family life, looking after his mother with quiet devotion. Such depth of trust and companionship is seldom seen in the history of art, echoing the great friendships where artistic vision was nourished not by worldly gain but by loyalty, empathy, and shared conviction.

Literati Ink in New Contexts

The literati tradition has always thrived on dialogue—between poetry, painting, and calligraphy; between solitude and community. Zeng extends this lineage into the twenty-first century, engaging in dialogues between China and the West. His landscapes of Yosemite, Hawaii, and Grand Prismatic Spring draw inspiration from the spirit of Su Shi (1037–1101), Ni Zan (1301–1374), and Dong Qichang (1555–1636), carrying forward their literati ethos into new geographies while making it resonate within a contemporary global setting. These works are not exercises in fusion but acts of renewal—anchored in fidelity to tradition while opening up to uncharted territories.

Among the cycle Eight Views of America, the Wisconsin School Run (Figure 2) stands out as a work where autobiography and literati tradition intersect. The composition does more than record an episode of daily life; it captures endurance in visual form. Created shortly after Zeng’s arrival in Milwaukee in 2021, the work expresses the dislocation of a family confronting an unforgiving Midwestern winter without the ease of a car. In this scene of ice-slick streets and cutting winds, Zeng carries his daughter while walking backward into the storm, his body itself becoming a shield.

In recalling the gesture, Zeng noted how the act of reversing direction—moving against the expected flow—revealed a new dimension of calligraphic motion. Yet the significance of the painting lies less in technical revelation than in the way adversity is transformed into aesthetic language. The work exemplifies the literati ethos of transforming hardship into cultivation, positioning resilience as a mode of artistry. By rendering a moment of parental care as a scene of disciplined struggle, Wisconsin School Run reinterprets the literary conviction that brush and life are one continuous practice.

Curatorial Activism

Zeng’s move to the United States in 2021 added another dimension to his practice. At the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, he curated Open Parameters: Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Chinese Calligraphy and Painting from the Zhou Cezong Donation (Figure 3). The exhibition reframed modern literary works not as static relics but as evidence of a living, evolving tradition. It was here that Zeng embraced what art historian Maura Reilly calls curatorial activism—the idea that exhibitions can challenge dominant narratives and restore marginalized voices to the cultural conversation.

Photo Courtesy: Jingwei Zeng (Opening Ceremony of Open Parameters, April 13th, 2023, Emile H. Mathis Gallery,University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee.)

For Zeng, this activism addresses two fronts: correcting Western misreadings of Chinese art and confronting the decline of literati culture in China itself. Too often in American academia, Chinese painting is interpreted without the grounding of poetry or calligraphy, stripped of the “three perfections” that give literati art its meaning. Zeng’s interventions—whether curating, teaching, or even writing letters in English with a brush—reinsert literati practice into global discourse as an integrated, living art form.

Beyond the Gallery

Zeng’s activism extends outside the white cube. In workshops at museums and universities across the U.S., he places the brush in others’ hands, inviting them to experience ink as reflection, poetry as thought, and calligraphy as dialogue. At the same time, he reverses the current of exchange: through WeChat, he introduces Western masterpieces to Chinese audiences, while on YouTube (The Literati Lens), he speaks in English about Chinese art for global viewers. This bilingual, bi-directional practice embodies cross-cultural curation not as theory but as daily work.

Toward an Extraordinary Tour

The Hong Kong exhibition gathered decades of labor into a coherent statement. Alongside Zeng’s own works were inscriptions from thirty prominent cultural and artistic figures, reviving the millennia-old literati practice of dialogue between brush and spirit. These inscriptions were not mere adornments, but integral acts of intertextuality—where painting and poetry intertwine, where colophons echo artistic integrity, and where community celebrates creativity. In this tradition, the artwork becomes not a solitary declaration but a shared cultural fabric, linking past and present, artist and audience, individual vision and collective voice.

The title, An Extraordinary Tour of Art (茲游奇絕), borrows from Su Shi’s verse on surviving a perilous sea voyage. For Zeng, the line resonates with his own trajectory: hardship transformed into resilience, solitude into vision, tradition into global dialogue. It also reflects the human trust that has sustained him—from family sacrifice to Yang Longqiang’s rare and historic support—showing that even in an age of markets, art can still be carried by faith and friendship.

Summary

Zeng’s career demonstrates that literati art is not an anachronism but a resource—one that can still shape global conversations about heritage, identity, and cultural justice. His projects show that curating is not neutral: it is a position, a responsibility, and sometimes an act of resistance. In refusing both the commercialization of art and the erasure of tradition, Zeng has built a practice that is at once rooted and transnational, scholarly and activist.

An Extraordinary Tour of Art is not just the story of an exhibition. It is the story of how literati ink, carried across oceans and strengthened by rare bonds of trust, can still find its way into the future.